Impact Test – Charpy V-Notch Test

Introduction

In engineering applications where structures are subjected to dynamic loads, impacts, or low temperatures, it is critical to ensure that materials possess not just high strength, but also the ability to absorb energy without sudden fracture — a property known as toughness.

Impact testing serves as an essential method to evaluate this toughness, and among various techniques, the Charpy V-Notch (CVN) Test is the most widely used. The test helps determine whether a material will behave in a ductile manner, absorbing significant energy and deforming plastically, or in a brittle manner, fracturing suddenly with little energy absorption.

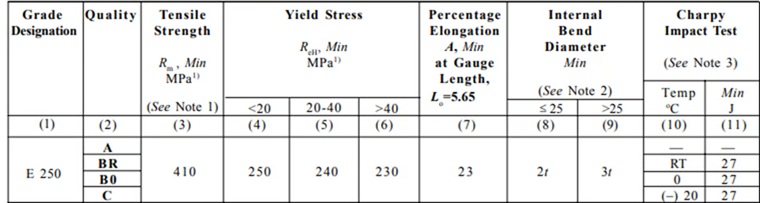

Standards like IS 2062 (Hot Rolled Medium and High Tensile Structural Steel — Specification) specify the minimum impact energy requirements for different temperatures to ensure material reliability.

Figure 1: IS 2062 Material Property Requirements

Figure 1: IS 2062 Material Property Requirements

As Per IS 2062 Impact Testing Requirements

- Impact testing is normally carried out on products having a thickness/diameter ≥ 12 mm.

- If specified in the order, impact tests may also be carried out on thinner products (less than 12 mm), following IS 1757 dimensions.

- A V-notch test piece is used, and the result is the arithmetic mean of three specimens taken side-by-side from the same product.

If the average of the three tests:

- Fails by ≤ 15% of the specified minimum — three additional test pieces are tested. The new average of all six results is considered.

- The thickest section is tested first; if it passes, the entire cast is accepted. If it fails, progressively thinner sections are tested until a passing thickness is found.

How the Charpy V-Notch Test is Performed

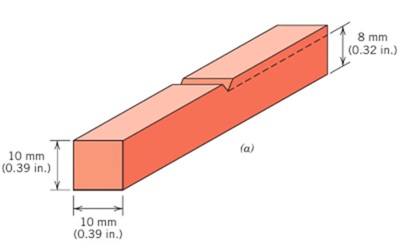

A test specimen is prepared in the shape of a bar with a square cross-section and a precisely machined V-notch at its center.

Figure 2: Standard Charpy V-Notch Specimen Dimensions

Figure 2: Standard Charpy V-Notch Specimen Dimensions

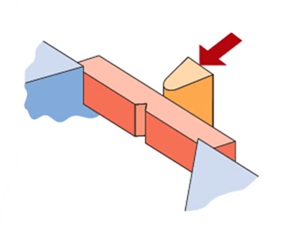

The specimen is placed horizontally between two anvils on the testing machine, with the notch facing away from the pendulum impact.

Figure 3: Charpy Test Setup

Figure 3: Charpy Test Setup

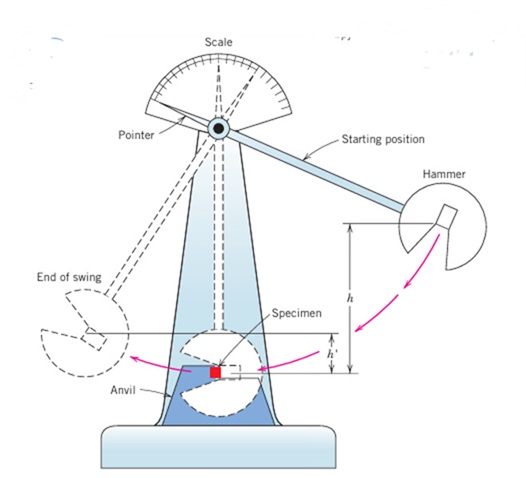

- A weighted pendulum hammer is raised to a fixed initial height h, storing potential energy.

- The notch acts as a stress concentrator, promoting fracture at a specific point.

- After fracturing the specimen, the pendulum continues to swing upward to a reduced height h’.

- The difference in height between the start h and end h’ positions is used to calculate the energy absorbed by the specimen during fracture.

- The absorbed energy value provides a direct measure of the material’s impact toughness.

Figure 4: Pendulum Mechanism

Figure 4: Pendulum Mechanism

Impact Energy Calculation:

Impact Energy = mgh - mgh’

Where:

- m = mass of the pendulum

- g = acceleration due to gravity

- h = initial height

- h’ = height after breaking the specimen

Ductile-to-Brittle Transition (DBTT)

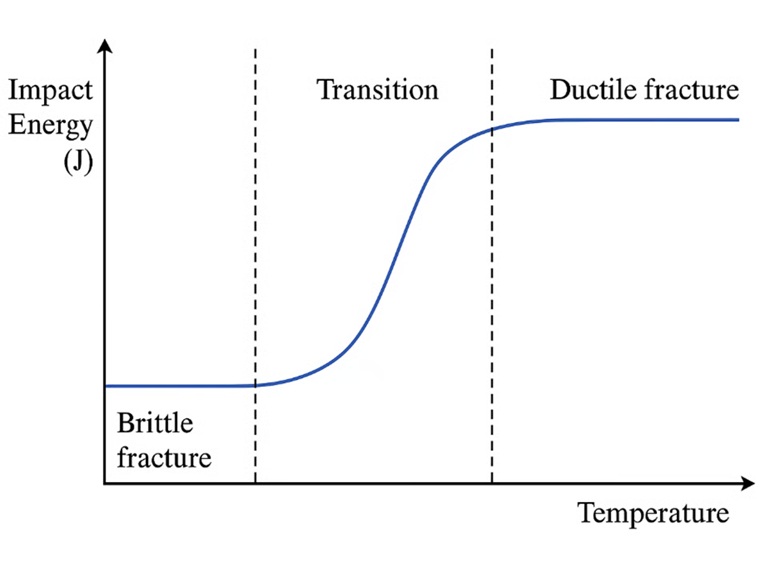

One of the main purposes of the Charpy V-Notch test is to find out if a material changes from ductile behavior to brittle behavior as the temperature decreases, and to identify the temperature range where this change happens. The ductile-to-brittle transition is closely related to how the material’s ability to absorb impact energy changes with temperature.

Figure 5: Typical Ductile-to-Brittle Transition Curve

Figure 5: Typical Ductile-to-Brittle Transition Curve

At higher temperatures, the material absorbs a large amount of energy and breaks in a ductile manner, meaning it deforms before fracturing. However, as the temperature drops, the absorbed impact energy falls sharply within a narrow temperature range. Below this point, the material absorbs very little energy and fractures in a brittle manner without much deformation.

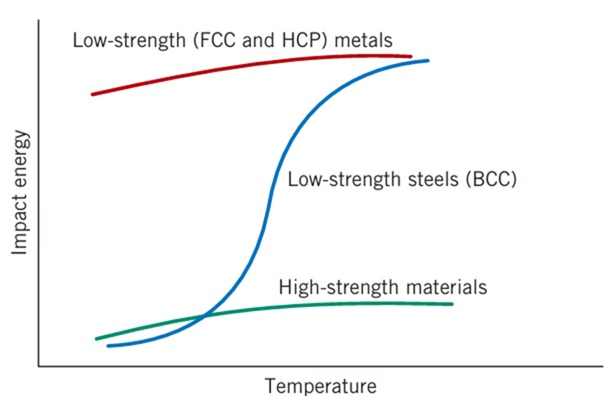

Figure 6: Effect of Crystal Structure on DBTT

Figure 6: Effect of Crystal Structure on DBTT

- Low-strength FCC metals (such as some aluminum and copper alloys) and most HCP metals do not exhibit a ductile-to-brittle transition, as shown by the upper curve. They retain high impact energies even at lower temperatures, meaning they remain tough across a wide temperature range.

- High-strength materials, such as high-strength steels and titanium alloys, are represented by the lower curve. Their impact energy is relatively insensitive to temperature, but remains low, indicating that these materials are brittle at all temperatures.

- The middle curve represents materials that experience a characteristic ductile-to-brittle transition, where impact energy drops sharply over a narrow temperature range. This behavior is typical for low-strength steels with a Body-Centered Cubic (BCC) crystal structure.

For low-strength steels, the ductile-to-brittle transition temperature is influenced by both the alloy composition and the material’s microstructure.

- As grain size decreases, the ductile to brittle transition temperature (DBTT) increases, meaning that materials with smaller grains become brittle at lower temperature. Hence, refining the grain size both strengthens and toughens steels.

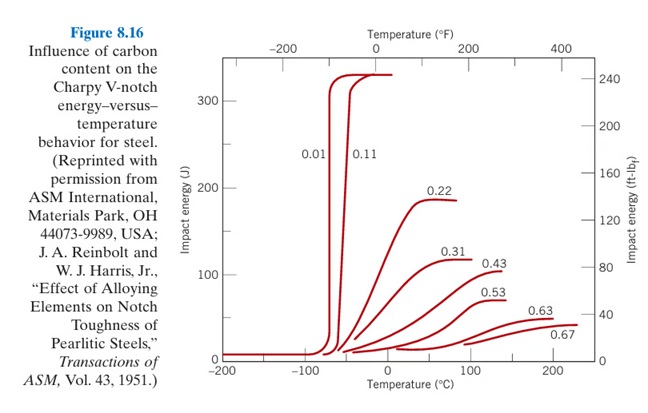

Figure 7: Effect of Carbon Content and Grain Size on Impact Energy

Figure 7: Effect of Carbon Content and Grain Size on Impact Energy

- Increasing the carbon content raises the transition temperature, even though it improves the strength of the steel. As a result, the steel becomes more brittle at higher temperatures, as reflected in the impact energy behavior shown in the figure.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the DBTT (Ductile-to-Brittle Transition Temperature) is an important factor to consider when choosing materials for applications where temperature matters. It’s good to know that there are ways to adjust this transition point to fit the needs of the application. For example, changing the material by refining its grain size, reducing carbon content, or making its structure more uniform can help the material stay flexible at lower temperatures.

References:

- Material Science And Engineering An Introduction by William D. Callister , Jr. & David G. Rethwisch

- IS 2062 : Hot Rolled Medium And High Tensile Structural Steel

- IS 1757 (1988): Method for charpy impact test